Scorecard Methodology

Research Design

The purpose of this research is to understand the challenges refugees face when attempting to access safe and lawful work. Through this research, we provide an understanding of legal frameworks protecting the rights of refugees to work, practical barriers to gainful employment, and opportunities to improve these rights in law and in practice.

Scoring Methodology

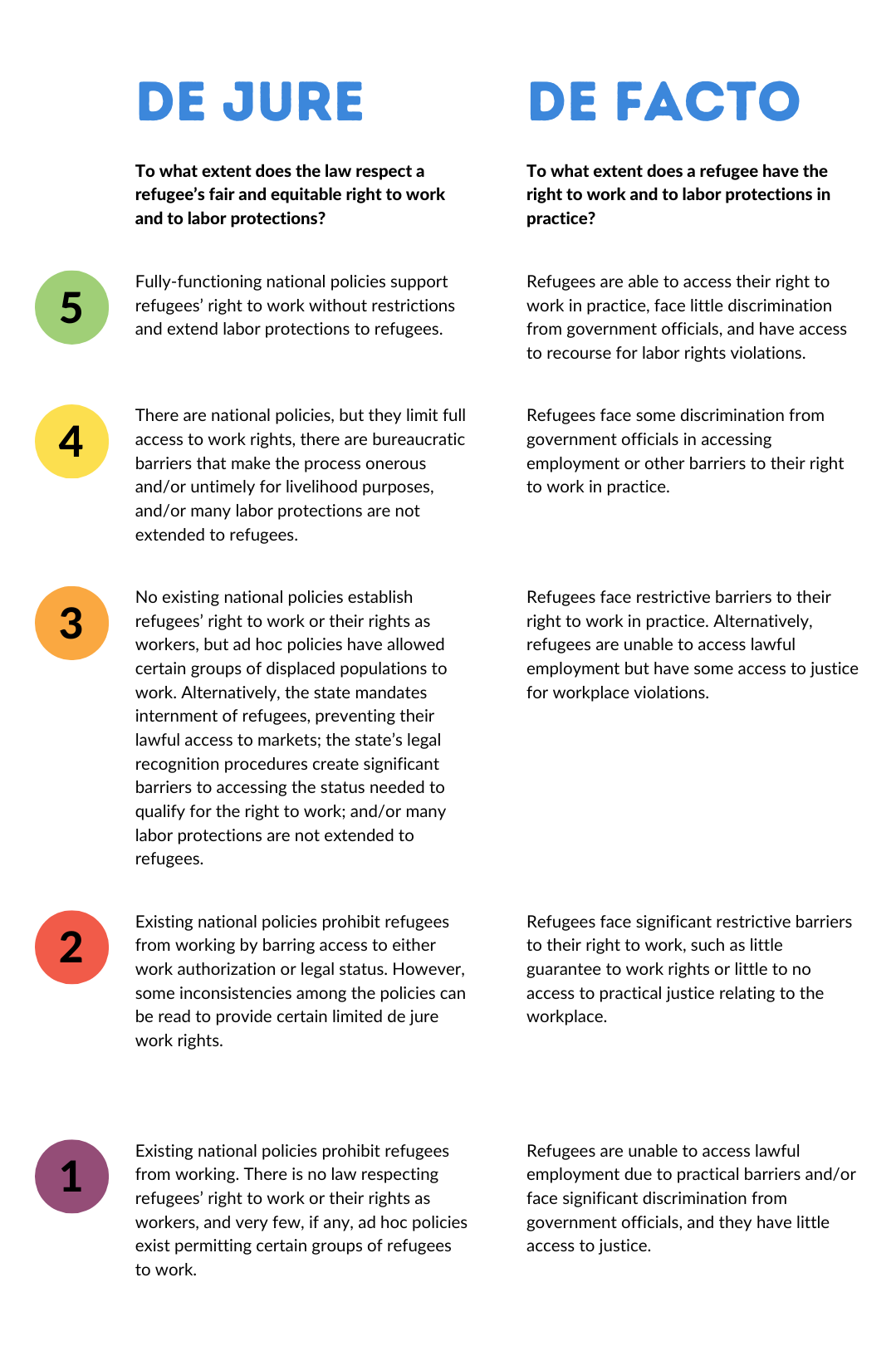

For each country, both de jure and de facto conditions are rated on a scale of green-to-purple as below. The de facto score determines the final score on a scale of green-to-purple for each country.

More information can be found in the report methodology as well as Annex 3 of the report.

Research Approach

In order to track and analyze the current situation of refugee work rights in any given country, we examine different dimensions of work rights both in law (de jure) and in practice (de facto) across 51 countries. These 51 countries were collectively hosting 87 percent of the world’s refugee population at the end of 2021. Combining legal documents, country-level reports, news articles, and input from more than 200 practitioners with knowledge of refugees’ livelihoods and use of services, we evaluate the de jure and de facto situation within a standardized framework.

We use the term “refugees” in this report to refer to all foreign-born people forcibly displaced by persecution or conflict and their descendants who are not citizens. The term includes those who are recognized or unrecognized refugees, asylum seekers, and other forcibly displaced populations, such as “Venezuelans displaced abroad,” in the country. We adopt this definition in order to standardize across countries, since the proportion of refugees, asylum seekers, and individuals in other categories varies significantly, and a comparison of standards for status determination is outside the scope of this report.

De Jure Right to Work

Question: To what extent does the law respect a refugee’s right to work and/or right to self-employment?

- Is the country a signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol?

- If yes, has this country made a reservation to Articles pertaining to the right to work & self-employment, being 13, 17, 18, 19, 24, or 26 in the Convention?

- Is the country a signatory to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights?

- If yes, have they made reservations to Articles pertaining to the right to work, being 6, 7, 8, or 9 of the Covenant?

- If a regional refugee law/convention/declaration is relevant, is the country a signatory?

- Is there a national law that protects a refugee’s right to work? If not, is there a relevant policy?

- To what extent does national law or policy conform with relevant regional and international norms?

- Is there discrimination in law or policy between refugee populations?

De Facto Right to Work

Question: To what extent does a refugee have the right to work and to labor protections in practice?

- Are refugees able to obtain work permits for formal, wage employment in practice?

- Do formal businesses hire refugees without permits in practice?

- How easily can refugees acquire business permits relative to citizens in practice?

- How free are refugees to operate businesses without permits in practice?

- How free are refugees to travel domestically in practice?

- How free are refugees to choose their place of residence in practice?

- Can refugees access recourse for workplace violations (i.e. if their employers do not pay them) through government institutions?

A detailed explanation of the methodology and a copy of the survey that was conducted with practitioners is available in Annex 3 of the Report.

Data Collection

Country Selection

Between March and December 2021, we conducted a survey among practitioners with knowledge of refugees’ de facto livelihoods and use of services. We received 260 responses from 83 countries. Given the subjective nature of the questions, we include only countries from which we received at least three responses. 51 countries, with 216 survey responses in total, met this criterion and are therefore included in our research. The responses to our survey on the de facto right to work determined the sample of countries represented here.

These 51 countries accounted for 87 percent of the global population of refugees, asylum seekers, and Venezuelans displaced abroad in 2021. Our sample includes the top 22 refugee-hosting countries globally and 37 of the top 50. Nevertheless, this set of countries is not fully representative of the global refugee population, as the remaining 13 percent of refugees may face circumstances that differ from those in the countries presented here. We therefore do not make inferences about the remaining populations, nor the refugee population as a whole.

De Facto Research

Information on the de facto right to work is gathered primarily through an international survey.

We designed the survey in English and translated it into French and Spanish. It was then circulated to international and local NGOs, refugee-led organizations, NGO networks, and multilateral institutions to reach a variety of people with different perspectives.

The individuals who responded represent a range of experiences in the humanitarian and development sectors. The large and diverse global response, however, still leaves a number of limitations on the ability to directly interpret these data within each country. The people who chose to respond potentially have different opinions than might have emerged from a full survey of the country-based humanitarian sector, and even these practitioners have limited insights into most refugees’ daily experiences.

The questions covered a range of topics relating to refugees’ rights and access to services within their host country. We use a government’s treatment of its citizens as the benchmark in order to isolate the discrimination faced by refugees in particular; for example, we ask how easily refugees can acquire business permits relative to citizens.

Many questions are rated on a 1 to 5 scale, and we accompany the numerical choices with a general definition to standardize across respondents and contexts. For example, the first question is:

On a scale of 1 to 5, how free are refugees to travel in practice?

- Refugees cannot leave their neighborhood or camp, and permits to travel are nearly impossible to obtain.

- (The situation is between 1 and 3.)

- Refugees travel, but they are regularly harassed and occasionally arrested by authorities when outside their residence. Alternatively, some refugees travel freely, while others have their movements restricted by camp boundaries, checkpoints by authorities, etc.

- (The situation is between 3 and 5.)

- Refugees travel freely in practice without interference from the government.

As a starting point, we used the median or most common response to reduce the influence of the highest and lowest scorers on each question. Two staff members then independently reviewed each country’s situation using available secondary sources such as news articles, NGO profiles, and government reports to determine a final score.

De Jure Research

Information on the de jure right to work is gathered primarily through desk research of national, regional, and international conventions and includes the following sources:

- Government databases at the national, regional, and local level

- Reports from NGOs working directly with refugees

- International and intergovernmental organizations in the humanitarian/refugee issues sector such as UNHCR and IRC

- Online databases such as Refworld

- Reliable News Sources such as BBC and Al Jazeera

- Academic Journals

Information in the “Country Facts” table was obtained from UNHCR’s 2021 Refugee Statistics. Data is for those classified as refugees, asylum seekers, and Venezuelans displaced abroad as defined by UNHCR.